In 1976, a year after he

joined the Supreme Court, Justice John Paul Stevens wrote in a

gender discrimination case, Craig v.Boren,

“There is only one Equal Protection Clause. It requires every State to

govern impartially. It does not direct the courts to apply one standard of

review in some cases and a different standard in other cases.”

Though our dear Justice Stevens no longer serves on the

Court, Justice Anthony Kennedy may well follow his words if Kennedy ends up

writing the majority opinion striking down same-sex marriage bans in Obergefell v. Hodges. The Court will be

hearing oral arguments in the case tomorrow, and observers and journalists (and

bloggers!) will be paying close attention to anything Kennedy may say. At the

same time, few close observers doubt that Kennedy will rule for the plaintiffs in

these cases. The big questions will be whether the majority will include more

than five justices (see these

other

posts on this blog) and what rationale the majority opinion will adopt in

striking down same-sex marriage bans.

If the Court does divide 5-4, Kennedy will undoubtedly

assign himself the majority opinion. What constitutional basis will Kennedy use

to side with same-sex couples? Kennedy was maligned by some for his opinion in U.S. v. Windsor, the 2013 precursor to Obergefell which struck down the main

section of the Defense of Marriage Act, for failing to articulate and apply a

clear Equal Protection standard to DOMA. Unsurprisingly, Justice Scalia

criticized Kennedy’s reasoning, calling it “an opinion with such scatter-shot

rationales...federalism noises among them,” but even some liberal

observers were disappointed or confused that Kennedy declined to adopt a clear level of scrutiny. Rather, Kennedy writes that DOMA “violates basic due process and equal protection

principles,” without offering much more by way of explanation (other than the

aforementioned “federalism noises”). Yet, as Justice Stevens

pointed out in 1976, there is only one Equal Protection Clause, and nothing

requires a majority to use the previously articulated standards in making a

judgment. Kennedy may have been adhering to that concept to avoid getting to the more complicated question of scrutiny.

Looking back a decade before Windsor, Kennedy largely avoided the

Equal Protection argument in his majority opinion in Lawrence v. Texas (2003), which struck down state sodomy bans.

Instead, he ruled on the basis of substantive due process, stating that any

private consensual sexual conduct between adults is protected from criminal

sanction by the word "liberty" in the Fourteenth Amendment. To be sure, his

opinion in Lawrence focused on the

harm such statutes did to gay people, writing that the “State cannot

demean their existence or control their destiny” by criminalizing their sexual

conduct. Even in making this major liberal ruling, though, Kennedy seemed

hesitant to abandon his conservative instincts, choosing simply to expand what

is covered by “liberty” under the Due Process Clause, rather than expand Equal

Protection to include an additional group.

In Romer v. Evans (1996), the Court struck down a Colorado

constitutional amendment which prohibited anti-discrimination laws or policies protecting

gays, lesbians, or bisexuals at the state or local level. The amendment had

passed in response to several localities passing such anti-discrimination laws.

Writing for a six-member majority, Kennedy vaguely applies a rational basis

test to the Colorado amendment and finds it unrelated to any legitimate governmental

interest. But he does not clearly adopt the rational basis test; instead, he

writes that even if the Court were to adopt this most lenient standard of

review—rational basis review—the amendment would be struck down. As he would

later do in Windsor, Kennedy is

invoking the concept of Equal Protection in striking down the amendment, yet he

does not make clear whether a higher level of Equal Protection does or should apply to

classifications based on sexual orientation in general. This may point to a

tension between Kennedy’s personal feelings toward gay people—whom he likely

believes deserve equal treatment—and his

judicial leanings—not to expand areas of the law too far, particularly when

it comes to Equal Protection.

What does this mean for Obergefell? Both questions presented mention

the Fourteenth Amendment generally, without specifying clauses, though most of the

cert petitions invoked Equal Protection and/or Due Process. So the door is open

to different possibilities. Having avoided adopting a clear Equal Protection standard for nearly

20 years, it seems unlikely Kennedy would do so now. Yet, it would be almost

irresponsible to strike down state statutes or amendments on this major issue

by merely invoking Equal Protection “principles.” Might Kennedy opt for Stevens’

“one Equal Protection Clause” idea? Perhaps. But Kennedy loves freedom. And

liberty. Thanks to his love of freedom, we now have

presidential campaigns that cost billions of dollars. And because “[l]iberty finds no refuge in a jurisprudence of doubt,” he voted not to overturn Roe v. Wade in 1992. Assuming he stakes out some kind of clear position in Obergefell, I suspect it will be under the guarantee of "liberty" in the Due Process Clause.

In Hollingsworth v. Perry (2013), the companion case to Windsor dealing with California’s Prop

8, Kennedy dissented from the majority’s ruling that the plaintiffs did not

have standing to sue and argued that the Court should reach the merits of the

case. In his dissent in Hollingsworth,

Kennedy writes, “Freedom resides first in the people without need of a grant

from government.” Though he was referring directly to the issue of

standing, that line could just as well have been from his imagined majority

opinion striking down same-sex marriage bans. If his past opinions, on both gay

rights and other issues, are any indication, Kennedy will feel compelled to

rule that the “liberty” of the Due Process Clause includes the freedom of two

adults to marry, irrespective of their sexual orientation or gender. As a

conservative, Kennedy will hesitate to recognize gays and lesbians as a new class

under the Equal Protection Clause, yet he will be happy to righteously bestow

liberty upon them through the Due Process Clause.

All of that being said, I

personally hope that Chief Justice Roberts joins the majority and writes the majority

opinion (or hands it off to Justice Ginsburg?),

because as I’ve expressed on a different blog, Justice Kennedy is, um,

not my favorite person in the world and I’m a little tired (okay, very tired) of

him getting all the credit on gay rights. And if that happens, everything I wrote

above will be largely irrelevant. We'll find out soon enough!

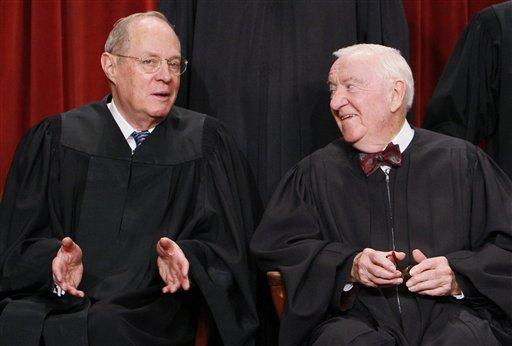

| I'll use this image whenever I possibly can. |

No comments:

Post a Comment